Kōsaku Yamada: The First Japanese Conductor at Carnegie Hall

This digital exhibit, presented by the Digital Museum of the History of Japanese in New York (DMHJNY) in collaboration with Carnegie Hall, revisits Yamada’s time in New York and his pivotal Carnegie Hall appearances of 1918–1919.

This event forms part of Carnegie Hall’s Spotlight on Japan.

Prelude

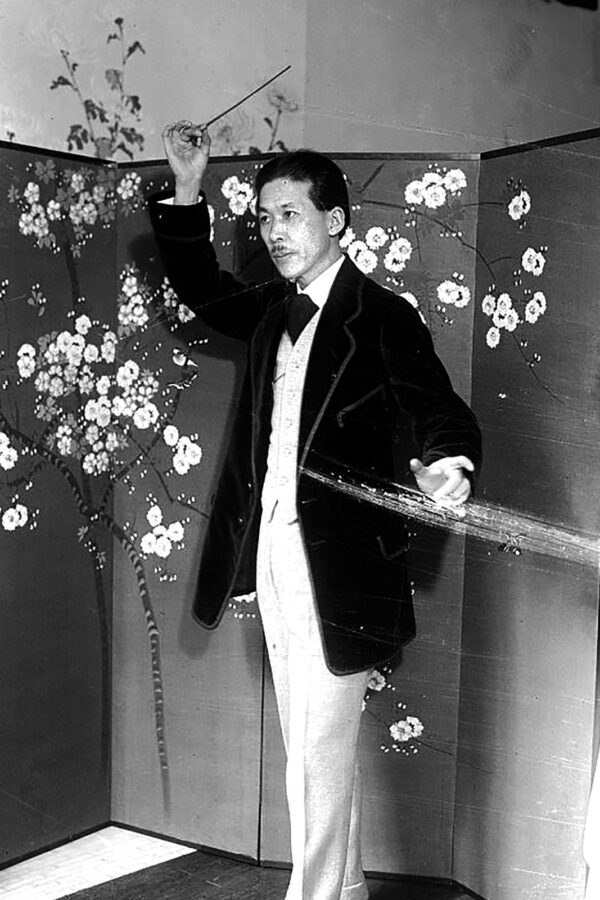

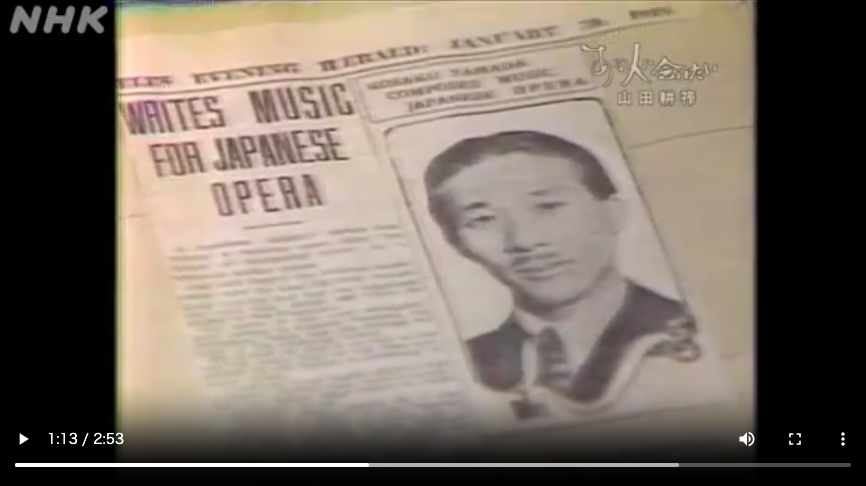

In November 1918, composer Kōsaku Yamada (1886–1965) (山田耕筰) arrived in New York City—then emerging as the cultural capital of a new postwar world. Within months, he made history as the first Japanese musician to conduct and perform his own works at Carnegie Hall, introducing American audiences to a distinctly modern vision of Japanese music. His performances marked a turning point in early twentieth-century cultural diplomacy, bridging Japanese and Western classical traditions through art.

Berlin Years (1910-1914)

While studying in Berlin under Max Bruch at the Königliche Akademische Hochschule für ausübende Tonkunst, Yamada immersed himself in the currents of European modernism. Supported by Baron Koyata Iwasaki, he encountered the new musical languages of Richard Strauss, Alexander Scriabin, and Arnold Schönberg, which transformed his Romantic sensibility into one informed by harmonic experimentation and formal innovation.

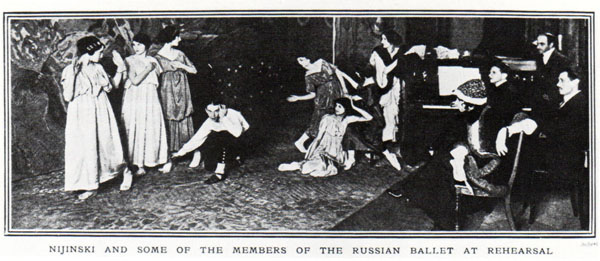

Yamada attended performances of Nijinsky’s L’Après-midi d’un faune in 1912, witnessing the avant-garde interplay of rhythm and gesture that paralleled his search for a modern Japanese sound. Works from this period—Madara no Hana (Flower of Madara) and Kurai Tobira (The Dark Gate)—blend Western orchestral form with Japanese imagery, marking the birth of his East-West musical synthesis.

Listen to Kosaku Yamada: Symphony in F “Triumph and Peace” (1912)

New York in 1918: An Allied Stage

Two Allied nations, France and Japan, presented their music to New York in two consecutive nights in 1918 and 1919. Yamada’s concert followed a French orchestral performance, drawing musicians from the Metropolitan Opera, the Philharmonic, and the Symphony Societies, joined by over 100 voices from the New Choral Society. The review by the New York Times (Oct. 17, 1918) called it “the first meeting of East and West as allies in art on American soil.”

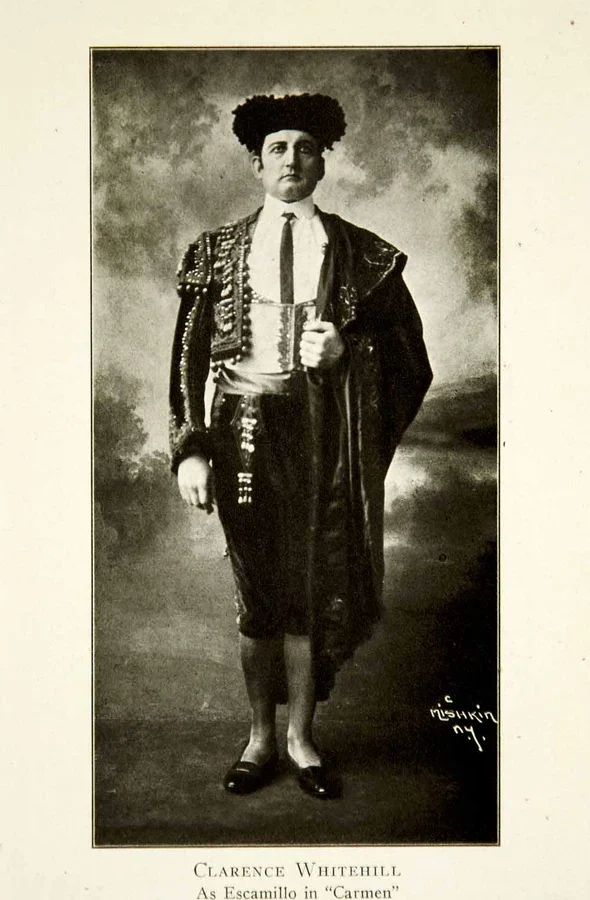

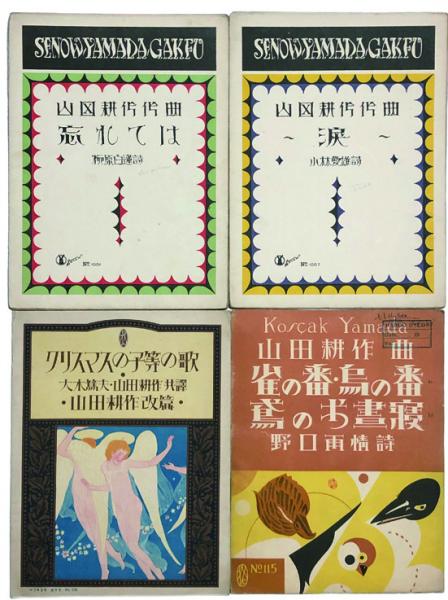

“Japanese Conducts Own Native Works” — published in The New York Times on October 17, 1918 — documents the landmark night when Kōsaku Yamada became the first Japanese composer-conductor to lead a full American orchestra and chorus at Carnegie Hall. The article describes how musicians from the Metropolitan Opera, the Philharmonic, and the New Choral Society performed an entire program of Yamada’s works, from Festival of Autumn to The Dark Gate and Flower of Madara. Reviewers praised his “swift command” and “modern orchestral tints,” comparing his disciplined artistry to that of Hokusai. Baritone Clarence Whitehill sang Japanese art songs, and during intermission Jiuji Kasai linked the concert to the wartime alliance between Japan and the United States, declaring that “Japan speaks to you through Mr. Yamada in a language universal to your hearts.” Attended by Ambassador Viscount Kikujirō Ishii, Dr. Jōkichi Takamine, and New York patrons such as Otto Kahn and Jacob Schiff, the event was celebrated as the first artistic meeting of East and West “as allies” on American soil — transforming Yamada’s concert into both a musical triumph and a diplomatic milestone.

Read the full article at the New York Times Times Machine

Yamada conducted with “swift command and admirable presence,” while his compositions combined Japanese lyricism with “every modern orchestral tint, from his French teachers to the mid-European despots of din.” His economy of melody was likened to the ukiyo-e artist Hokusai’s disciplined brushwork, revealing both restraint and mastery.

Program and Repertoire

The evening’s program was entirely devoted to Yamada’s own music:

- Festival of Autumn (choral work from his Leipzig student days)

- The Dark Gate and Flower of Madara (tone poems inspired by Shogunal and Buddhist imagery)

- Petite Suite — from Kyoto folk dances, Tōkaidō travels, and Nagasaki celebrations (“the first suite written by an Oriental,” the program claimed)

- Choral Symphony from Maeterlinck’s Marie Magdalene

- Two Legends of Old Japan

- Coronation Prelude on the Japanese imperial anthem “Kimigayo.”

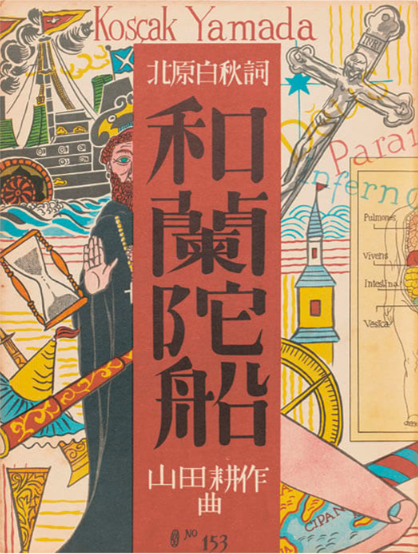

The American baritone Clarence Whitehill sang Yamada’s songs — including “Fisher and Sea Gull,” “Flower Song,” and “Homeward Bound” — some in Japanese and some in English, to great applause. The review noted the audience’s delight in hearing Japanese lyrics performed by a Metropolitan star.

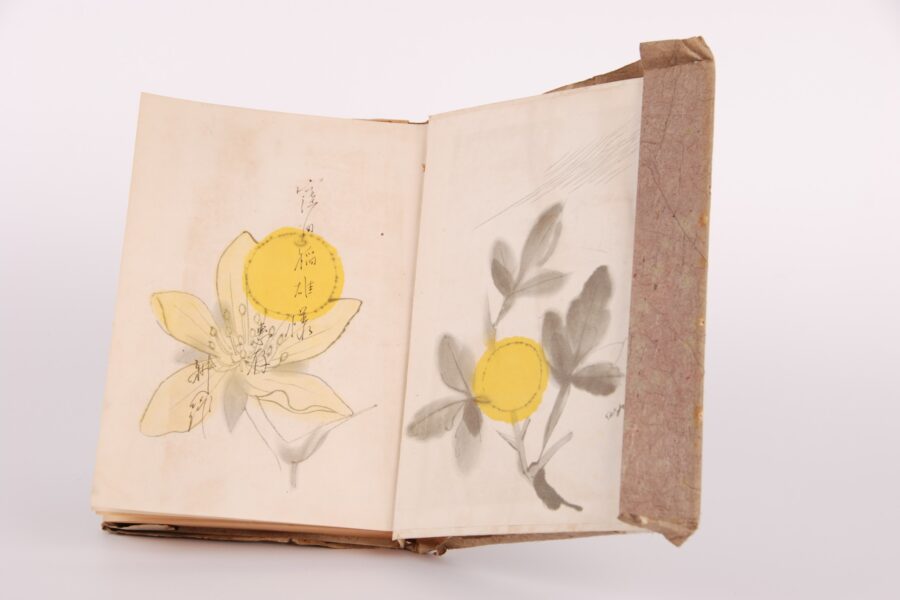

Kōsaku Yamada and Art

Renowned as Japan’s first fully modern composer-conductor and creator of Karatachi no Hana and Akatonbo, Yamada was also an advocate for the visual and performing arts. After returning from Berlin, he co-organized the “Sturm Woodcut Exhibition” (1914) with Keizō Saitō, introducing European expressionism to Japan and influencing artists such as Kōshirō Onchi and Kiyoshi Hasegawa. His magazine Shi to Ongaku (Poetry and Music, 1922–) and collaborations with Hakushū Kitahara, Yumeji Takehisa, and Onchi further reveal his integrative vision of sound and image.

Musical Exchange and Cultural Diplomacy

Yamada’s New York period represented more than an artistic milestone—it was also an early experiment in trans-Pacific cultural diplomacy. His music embodied a cosmopolitan vision that resonated with contemporary ideas of peace and internationalism emerging after World War I. Through his concerts, Yamada challenged stereotypes of Japan as culturally isolated and introduced Western audiences to Japan’s modern artistic achievements.

Yamada also met and corresponded with American musicians, conductors, and journalists, establishing networks that influenced later exchanges in the 1920s and 1930s. His success at Carnegie Hall inspired younger Japanese artists to study abroad and contributed to the gradual inclusion of Japanese composers in international concert repertoires.

Listen to Nagauta Symphony “Tsurukame” (1934)

Performed by the Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra, Nagauta Ensemble, Shamisen Ensemble, and Hayashi Ensemble, conducted by Takuo Yuasa, featuring Tetsuo Miyata (voice) and Tōru Ajimi (shamisen).

Composed by Yamada in 1934, this work fuses traditional Japanese Nagauta with the modern Western symphony. In this groundbreaking synthesis, Yamada juxtaposed the classical Tsurukame (by Rokuzaemon Kineya X, 1851), celebrating longevity through the crane (tsuru) and tortoise (kame), with orchestral counterpoint for double winds, strings, and harp. The result is a concerto-like dialogue between Japanese and Western musical idioms. Nagauta, developed in seventeenth-century Edo as accompaniment for Kabuki dance, combines voice, shamisen, fue, and percussion, drawing on the aesthetics of Noh, Jiuta, and Jōruri traditions. Its composite character made it an ideal medium for Yamada’s vision of cross-cultural expression. At its 1934 premiere, Yamada conducted the Nippon Broadcast Symphony Orchestra (today’s NHK Symphony) alongside master Nagauta musicians. The Nagauta Symphony “Tsurukame” remains a milestone of modern Japanese orchestral writing—an eloquent celebration of continuity between the nation’s classical arts and twentieth-century modernism.

Yamada During the War (1937–1945)

During the Asia-Pacific War, Yamada served as chairman of the Nihon Ongaku Bunka Kyōkai (Japan Music Culture Association)and founded the Music Volunteer Corps, organizing performances for soldiers and civilians. Though associated with wartime propaganda, he pursued the elevation of musical literacy and cultural dignity within artistic expression. His works Kamikaze (1940) and Kurofune (The Black Ships) exemplify the tension between national duty and artistic autonomy. Postwar critics debated these choices, but his career illustrates the complexities of creative life under state control.

The transformation of Japan’s musical institutions during the Asia-Pacific War was not limited to professional circles like Kōsaku Yamada’s Music Volunteer Corps (Ongaku Hōkōtai). Across the nation, school bands, youth orchestras, and civic choirs adopted military training structures and repertories drawn from army music traditions. These ensembles performed marches and anthems to inspire morale and express collective loyalty to the nation. This photograph of the Tōhō Commercial School Music Club captures the atmosphere of that era—when young musicians rehearsed and performed not only as artists, but also as symbolic participants in Japan’s wartime mobilization through sound.

After the War (1945–1965)

Following Japan’s defeat, Yamada faced criticism for his wartime leadership but devoted himself to rebuilding Japan’s musical culture. He resumed composition and conducting with renewed humanism. Works such as Omoide (Memories) and Umi no Koe (Voice of the Sea) reveal a shift toward lyrical introspection. He mentored emerging composers, promoted cultural exchange, and helped redefine postwar musical identity. By the time of his death in 1965, Yamada was recognized as both pioneer and reconciler—the musician who first brought Japan’s voice to the world.

His legacy endures at Carnegie Hall and beyond—as the musician who first gave Japan a symphonic voice on the world stage.

References

YouTube. “Kōsaku Yamada: Symphony in F ‘Triumph and Peace.’” Performed by the Japan Philharmonic Orchestra. Uploaded by Classical Music Channel, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sY7He5w_5cY.

YouTube. “Nagauta Symphony Tsurukame (1934).” Uploaded by Classical Music Channel, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eEou_EdZp-U.

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. Kōsaku Yamada, Portrait (1918–1919). https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/pnp/ggbain/27600/27699v.jpg.

Wikipedia Japan. “山田耕筰 (Yamada Kōsaku).” Last modified September 2025. https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/山田耕筰.

Pacun, David. “Thus We Cultivate Our Own World and Thus We Share: Kōsaku Yamada and the Modern Japanese Symphony.” American Music 24, no. 1 (Spring 2006): 67–94. University of Illinois Press. https://scholarlypublishingcollective.org/uip/am/article-abstract/24/1/67/261469.

Tokyo University of the Arts Archive Center. Rhapsody of Youth (若き日の狂詩曲). https://archive.geidai.ac.jp/en/8157.

Tochigi Prefectural Museum of Fine Arts. Yamada Kōsaku Exhibition. https://www.art.pref.tochigi.lg.jp/exhibition/t200111/index.html.

NHK Archives. “山田耕筰—交響曲や長唄交響曲などを作曲.” https://www2.nhk.or.jp/archives/articles/?id=D0009250124_00000.