Surviving The Storm

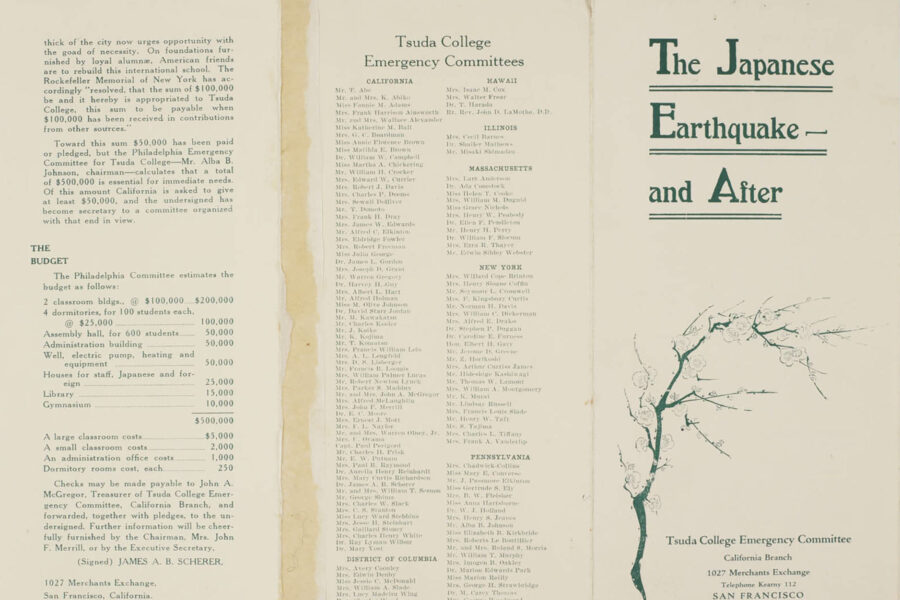

Tsuda College Emergency Committee

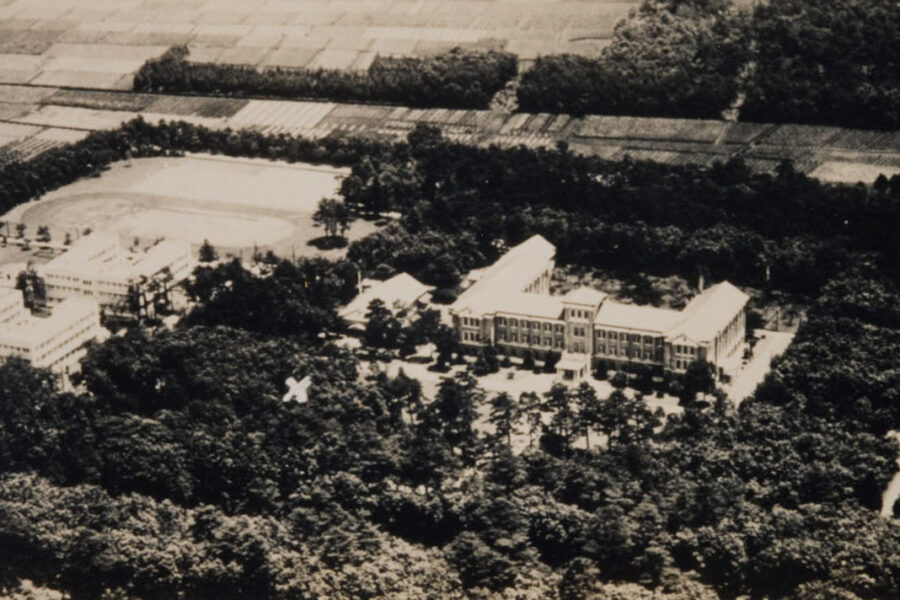

In the early 1900s, one of the few institutions of higher education for women in Japan was Tsuda College (originally known as the Women’s English School) in Tokyo. The school was named after its founder, Umeko Tsuda, who was educated in the U.S. and possessed close connections to the Quaker community. Tsuda College opened in the year 1900 and was a truly pioneering institution as one of the only places in Japan that provided women with advanced vocational training in fields other than domestic work. Over the next twenty years, the school grew in prestige as an elite institution of learning and produced prominent alumnae.

Students pose in the school yard in front of Joshi Eigaku Juku. Umeko Tsuda seated in the center of the front row, 1901, Courtesy of Tsuda University Archives

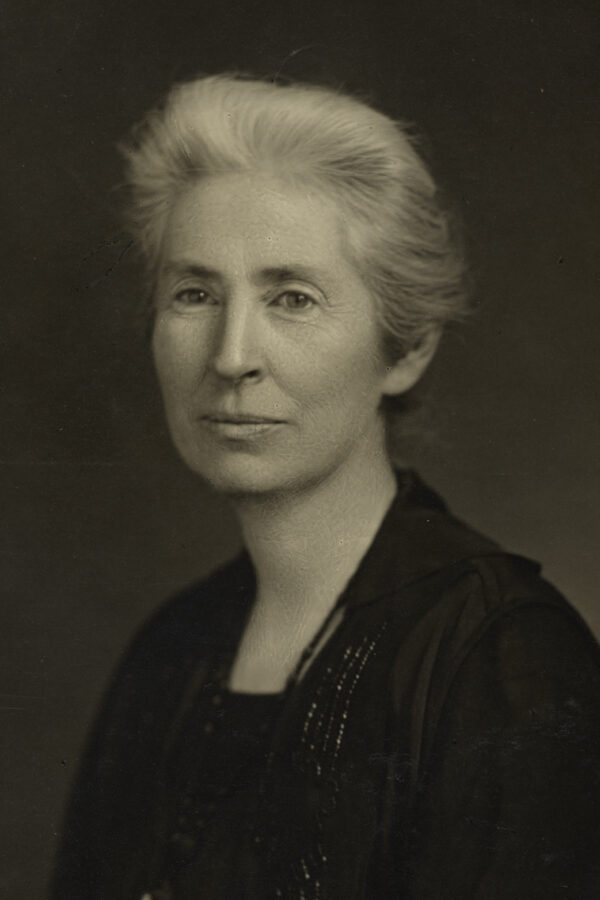

However, during the 1923 Great Kantō Earthquake—one of the largest natural disasters in modern Japanese history—Tsuda College’s facilities were completely destroyed. To ensure the survival of the school, New York philanthropists became involved in fundraising efforts at the behest of their Quaker friends, most notably Anna Hartshorne. Hartshorne, who was born in Philadelphia but had worked at Tsuda College for years, returned to the United States in 1924 to raise funds for its reconstruction. Through her Quaker network, Hartshorne established the headquarters of the “Tsuda College Emergency Committee” in Philadelphia. She knew, however, that any successful fundraising effort would require aid from New York as well. As it happens, she found just the help she needed in the form of wealthy philanthropist and activist Narcissa Cox Vanderlip.

Students and faculty stand in front of the remains of school building destroyed by a fire following the Great Kanto Earthquake, 1923, Courtesy of Tsuda University Archives

Deeply involved in the women’s suffrage movement, Narcissa Vanderlip was an influential figure in American progressive circles in the 1910s and ‘20s. Beyond suffrage, she was also committed to promoting peaceful relations between countries at a time when political tensions between the U.S. and Japan were rising. In truth, Vanderlip believed that these two issues were linked, and that improving the lives of women around the world was a means of achieving global stability and avoiding conflict.

She was one of a number of feminist leaders and activists who believed that efforts like the one to advance educational opportunities for women in Japan were significant not just for one country, but for international feminist movements as a whole. Many of these individuals employed global networks to improve the position of women in their own nations and around the world under the belief that a rising tide lifts all ships, and that improvements in this respect would result in a better, more productive society at large.

Although Vanderlip was not affiliated with the Society of Friends, her beliefs in promoting peace and advancing the status of women were also closely aligned with Quaker sentiments of the time.

Narcissa and her husband, Frank Vanderlip–a prominent banker, architect of the U.S. Federal Reserve System, and president of Japan Society–traveled to Japan in 1920 to work on strengthening the bond between the two nations. This was Narcissa’s first real exposure to Japan, and the experience deeply affected her. She came to feel personally invested in women’s movements in Japan, and her trip reaffirmed her belief that international solidarity was necessary for the advancement of feminist causes.

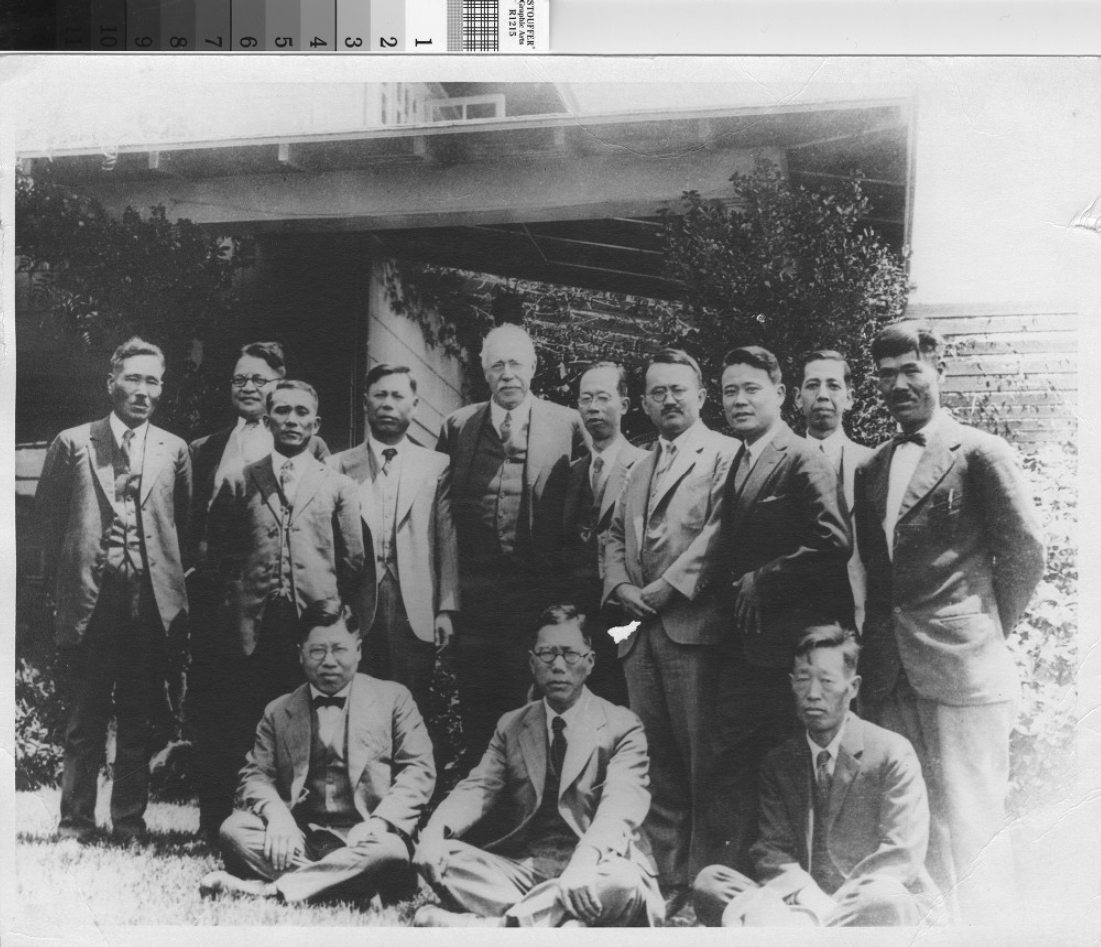

Frank Vanderlip with Dignitaries from Japan, 1928, Palos Verdes Library District

It is important to note that Narcissa, like many Western visitors to Japan at the time, harbored assumptions that most progressive efforts for women and education were attributable to Western, Christian influence. This was partly true in the case of Tsuda College, which she called “a curious mixture of America and Japan,” because Tsuda herself had based some of the curriculum on her experiences in the U.S. and Christian models of education. But in truth, Tsuda and others were often careful to balance Christian influences with Japanese methods of instruction and administration, sometimes to the chagrin of their Western benefactors. Despite the relatively narrow view of Japan that Narcissa developed as a result of her mistaken assumption that Christian influence must hold true broadly across the feminist movement in the country, her advocacy for Japanese women nevertheless aided them in the realization of their goals.

Mrs. Willard Cope Brinton

Mrs. Henry Sloane Coffin

Mr. Seymour L. Cromwell

Mrs. F. Kingsbury Curtis

Mr. Norman H. Davis

Mrs. William C. Dickerman

Mrs. Alfred E. Drake

Dr. Stephen P. Duggan

Dr. Caroline E. Furness

Hon. Elbert H. Gary

Mr. Jerome D. Greene

Mr. Z. Horikoshi

Mrs. Arthur Curtiss James

Mr. Hideshige Kashiwagi

Mr. Thomas W. Lamont

Mrs. William A. Montgomery

Mr. K. Murai

Mr. Lindsay Russell

Mrs. Francis Louis Slade

Mr. Henry W. Taft

Mr. S. Tajima

Mrs. Charles L. Tiffany

Mrs. Frank A. Vanderlip

Narcissa, Anna, and the rest of the New York branch of the Emergency Committee proved to be a capable team. Although they were only one of many chapters in the U.S., by 1926 they had successfully raised over $200,000 (roughly $1.7 million today), 40% of the total needed to rebuild the school. This, combined with the collective work of the other U.S. chapters, meant that the Committee reached its goal within only two years of campaigning, a testament to the dedication of the Quaker community and its New York friends.

Without Anna Hartshorne and the efforts of the New York community, it is possible that the most influential women’s college in Japan might not have survived past its 23rd birthday. The solidarity of these individuals across national and cultural boundaries helped to preserve a means for women in Japan to advance their own lives and push back against entrenched gender roles. And at the heart of these connections was Anna and the Religious Society of Friends, which guided the organizational structure for the Emergency Committee’s outreach.

In 1932, nearly a decade after the earthquake, construction of Tsuda College’s new campus was completed and its main building christened “Hartshorne Hall”. Thereafter, Narcissa and Frank Vanderlip continued to raise funds for the college and to promote closer relations between the U.S. and Japan. Although their efforts to promote peaceful diplomacy ultimately failed as the world plunged deeper into the throes of World War II, the Vanderlips’ legacy, as well as Hartshorne’s, lives on at Tsuda University, which remains one of Japan’s leading women’s universities to this day.