Postwar Policy

After the end of World War II, Japanese society underwent a number of changes in its government, economy, industry, and, of course, education. Many of these changes were overseen by the American occupation forces and the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, or SCAP. However, the Occupation’s relationship with Japan was not simply one of conqueror and conquered. In truth, there was a great deal of cooperation between SCAP and Japanese citizens who often found unique opportunities to implement their own ideas within the framework of the Occupation.

Two of these individuals, Michi Kawai and Ai Hoshino, were women educators with ties to the Quakers and to New York who were able to use Occupation efforts to solidify the position of women and their access to equal education. In addition, American educators from New York who were also under the guidance of Quakers like Hugh Borton and Gordon Bowles (both academics and Japan experts) played an important role in these reforms too, working hand in hand with Kawai, Hoshino, and other Japanese educators to bring about change.

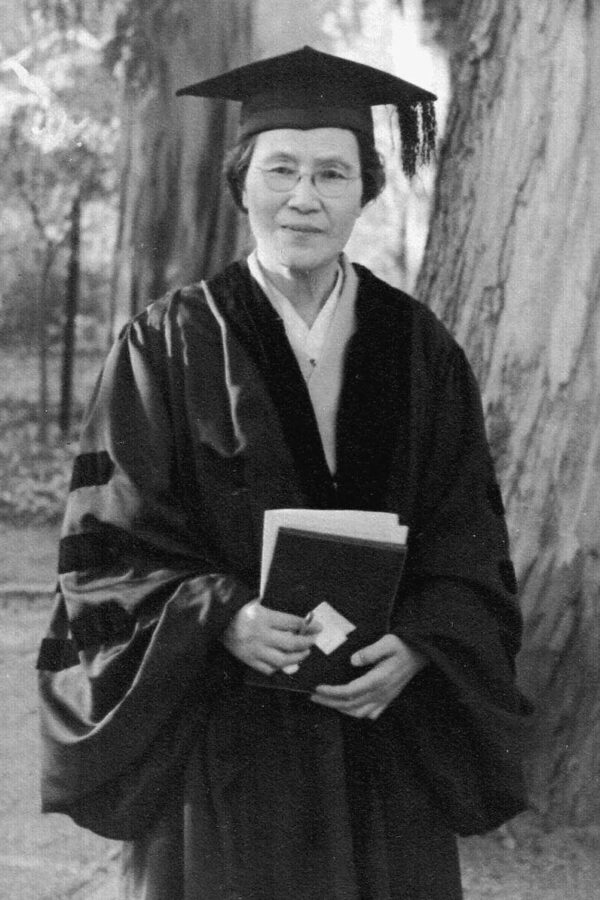

Michi Kawai (third from right) during her time as a Peace Envoy to the U.S., 1941, Courtesy of Keisen Jogakuen

Michi Kawai

Michi Kawai was an educator and internationalist who founded the Keisen Girls Academy and the Japanese branch of the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA). Throughout her career, she took an active role in the advancement of women in Japan and traveled throughout the world to promote this cause. In her youth, however, before she established her reputation as a capable leader, Kawai was a shy student who needed the careful encouragement of a teacher before she agreed to study abroad in the United States. Her teacher was Inazo Nitobe, a Japanese Quaker and intellectual who also advocated for a more global society and the advancement of women.

Kawai credited Nitobe with inspiring her to use her international experience to expand her ambitions. On her first trip abroad, he told her:

Foreign Delegates at the first Silver Bay YMCA Conference. Michi Kawai seated in front (right), 1939

Indeed, just as Nitobe prophesied, one of Kawai’s most foundational experiences would occur outside the walls of Bryn Mawr College, where she was enrolled as a student thanks to a scholarship from the Quaker community. In 1902, she was invited to attend a Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) camp in Silver Bay, New York, where she encountered a level of camaraderie and freedom among the young women that surprised and inspired her.

“Silver Bay gave me a glimpse of the bright, happy maidenhood of American girls in their upper teens, a period which seems to be left out of the lives of Japanese girls; for, carefree and happy though we are in our early teens, womanhood descends upon us suddenly. I coveted such a joyful experience, recreational, social, spiritual, for our girls.” – Michi Kawai

Kawai found inspiration in the variety of futures the other girls at the camp saw for themselves and began to contemplate how she could help to expand future opportunities for women in Japan. After Silver Bay, the YWCA became an integral part of Kawai’s life.

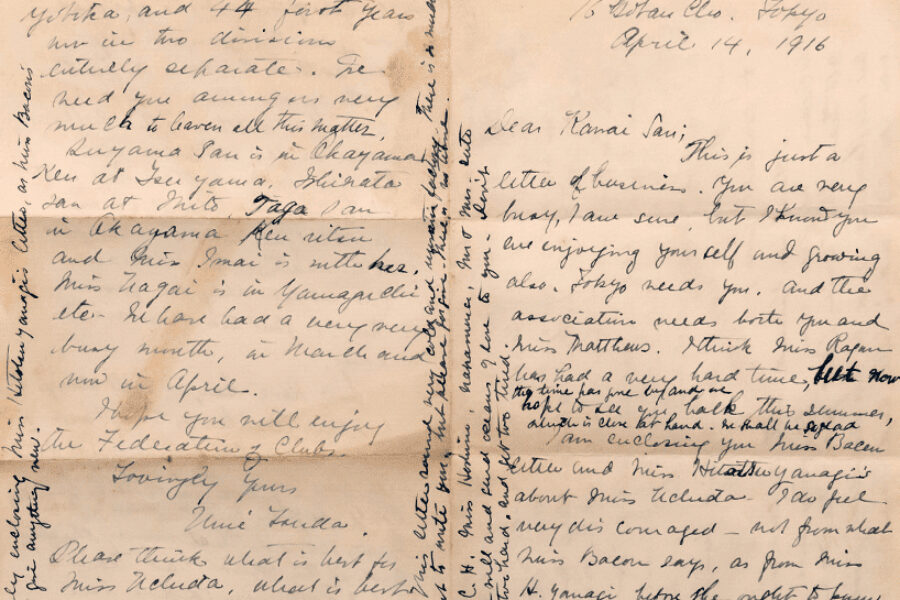

Upon her return to Japan, she became a teacher at Tsuda College, one of the few institutions of higher learning for women in Japan, which held deep ties to the U.S. Quaker community. She remained closely connected to the YWCA, however, and was a founding member of the organization’s Japan branch. She eventually became the national secretary, left her position at Tsuda College, and returned to New York once more in 1915 for a year of study at the YWCA’s National Training School. She remained a senior leader in the Association for the next decade, even as she undertook numerous other projects.

In 1927, she founded the Keisen Girls School in Tokyo, which naturally emphasized Christian and international studies–subjects that had been important to her since her early years with the Quakers in the U.S. She remained head of the Keisen School for the next two decades: through World War II and the postwar occupation. This made her a particularly experienced educator with extensive national and international connections at a time when SCAP was seeking individuals to help reform the nation’s educational system.

Kawai was quickly recruited alongside her former colleague from Tsuda College and fellow Quaker scholarship recipient, Ai Hoshino.

Ai Hoshino

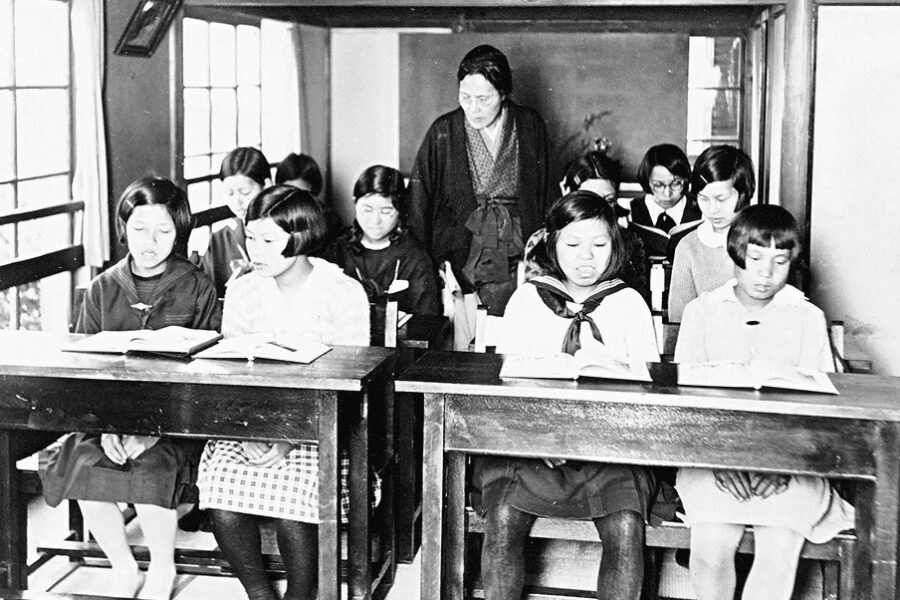

Ai Hoshino was a prominent Japanese academic who received her postgraduate education in New York City, served as president of Tsuda College, and was instrumental in securing official university status for women’s institutions of higher learning in the postwar era.

Hoshino originally came to the United States in 1906 under Quaker sponsorship after graduating from Tsuda College. While studying at Bryn Mawr College in Philadelphia, she lived with a Quaker family and was a frequent guest at the home of the Elkintons, the family of Inazo Nitobe’s wife, Mary Elkinton. Her relationship with the Elkintons would remain significant throughout her life as they were consistent supporters of Tsuda College, both financially and personally.

When she returned to Japan from the United States in 1912, she became an instructor at her alma mater, Tsuda College, and taught there for over fifteen years.

New York became a crucial part of Hoshino’s career when, in 1928, she traveled to the U.S. again to enroll in a master’s program at Teachers College, Columbia University in New York City. By successfully completing the program, Hoshino acquired the credentials necessary to assume the role of second president of Tsuda College when she returned to Japan the following year.

Hoshino presided over the college through turbulent times, such as the construction of the new campus after the Great Kanto Earthquake and the uncertainty of World War II. The lead-up to and progress of the war also put women’s education in a precarious position and prevented Hoshino from pursuing many of the reforms she felt were necessary to secure its future. However, her success as an educator, thanks in part to the advanced training she received in New York and her connections within the Quaker and academic communities on the East Coast of the U.S., gave her the opportunity to see many of her ideas put into practice after the war through her association with the 1946 U.S. Education Mission.

U.S. Education Mission (“The Stoddard Mission”)

Proposed in stages by many, including three prominent Quakers: Columbia University professor-turned State Department official Hugh Borton; Japan-born anthropologist and Syracuse University professor Gordon Bowles; and Japanese Minister of Education, student of Inazo Nitobe, and former Director of the New York Japanese Cultural Association Tamon Maeda, the 1946 U.S. Education Mission sent a number of American academics to assess the state of Japanese education and make recommendations to SCAP for reform.

Members of the 1946 Stoddard Mission to Japan. Front row starting fourth from left are women educators Emily Woodward and Virginia Gildersleeve, then President of University of Illinois George C. Stoddard (Chairman). Fourth and fifth from right are Pearl A. Wanamaker and Mildred McAfee Horton. Standing behind Gildersleeve is African-American educator Charles S. Johnson and to his left Catholic educator Roy J. Deferrari, 1946

Tamon Maeda, Proceedings of the Seventh Biennial Conference of the World Federation of Education Associations, Tokyo, Japan, August 2-7, 1937

George D. Stoddard

John N. Andrews

Harold Benjamin

Gordon T. Bowles

Leon Carnovsky

Wilson Compton

George S. Counts

Roy J. Deferrari

George W. Diemer

Frank N. Freeman

Kermit Eby

Virignia C. Gildersleeve

Willard E. Givens

Ernest R. Hilgard

Frederick G. Hochwalt

Mildred McAfee Horton

Charles S. Johnson

Isaac L. Kandel

E. B. Norton

Charles H. McCloy

T. V. Smith

David Harrison Stevens

Paul P. Stewart

Alexander J. Stoddard

W. Clark Trow

Pearl A. Wanamaker

Emily Woodward

These counterparts formed the Committee of Japanese Educators and were led by Shigeru Nanbara, the president of Tokyo Imperial University and a close friend of Hugh Borton. Michi Kawai and Ai Hoshino held prominent positions on the committee as well-known feminist scholars, and, like them, a number of other members had also been students of Inazo Nitobe, resulting in a strong Quaker influence on the Japanese side as well.

Before the mission’s arrival in Japan, Bowles and Borton had already contributed extensively to pre-surrender planning for the Japanese school system by drafting proposals that served as the basis for later State Department policies and laid some of the groundwork for the mission’s final report.

Today however, the Education Mission itself bears a controversial legacy. It is remembered for having a lasting impact on the development of postwar school policy, yet for being extraordinarily brief in duration. Among its many controversies were the speed with which its report was composed (the members spent only three weeks gathering information and one week writing the report), the lack of knowledge most of its members had about Japan (with the exception of Bowles), and its suggestion that the teaching of Kanji (traditional Chinese characters used in Japanese writing) be eliminated from the school curriculum.

However, there was significant disagreement within the mission on a number of items and Bowles was one of many who opposed the elimination of Kanji, for example. Furthermore, scholars have pointed out, that despite its shortcomings, much of the Stoddard Mission’s report and subsequent policies represented more than the hastily formed opinions of its brief visit. Beyond what Borton and Bowles had already contributed, much of the work was actually done by the Japanese advisers to the Mission who continued to work with the Occupation authorities afterward, and who had been making their own proposals for years beforehand.

In fact, by the time they were finished, Bowles estimated that 60% of the Mission’s report came from the Japanese side.

“…the [Japanese advisory] Committee included a number of liberal readers, several of whom had suffered in the past for their endeavors and were keenly aware of many of the problems to be faced in the future.”

– Gordon Bowles

Kawai and Hoshino were two such individuals who seized the opportunity to promote women’s education throughout the country. Both had been working with SCAP since late 1945 and had already been instrumental in drafting the “New Comprehensive Plan for Women’s Education Reform”, one of the early documents outlining the Occupation’s policy toward single-sex education. After the arrival of the Education Mission, they were able to continue this work, and although the final policies were not written by their hand, their influence can be felt throughout much of the report:

“[Junior high schools] should become coeducational, as rapidly as conditions warrant, the principle involved being as applicable at this level as in the primary schools.”

“Beyond the [junior high schools], we recommend the establishment of a three year [high school], free from tuition fees and open to all who desire to attend. Here again, coeducation would make possible many financial savings and would help to establish equality between the sexes…These schools should include academic courses leading to entrance to colleges and universities, as well as courses in home-making, agriculture, and trade and industrial education.”

“This obligation to assist the brightest students is greatly increased by the recently declared position on the rights of women. This bold and admirable move has settled the issue of equal rights in principle; it now is necessary to confirm the principle in action. In order that equality be generally true in fact, steps are necessary to insure to girls in earlier years an education as sound and thorough as that of boys. Then a good foundation for training in preparatory schools will place them on really equal terms with men for admission to the best universities.”

“Freedom of access to higher institutions should be provided immediately for all women now prepared for advanced study; steps should be taken also to improve the earlier training of women.”

Each of these are positions that Kawai, Hoshino, and a number of other Japanese liberals had been advocating for for years. With the changing politics of the postwar era, they finally had the opportunity to see them implemented, which they did with a noticeable sense of urgency. In her memoir Hoshino remarked,

“I thought, if we missed the opportunity, we would probably never have a chance again.” – Ai Hoshino

Many of the Mission’s recommendations would go on to become official policy in the years to come, including coeducation in primary schools, admission of women into standard universities, and recognition of women’s institutions of higher learning as full universities in their own right.

These landmark achievements were made by a coalition of Japanese and American educators, representing New York, the Religious Society of Friends, and in many cases both – all with a shared vision for the equal education of women in Japan.